WORDS: HENRY OWENS

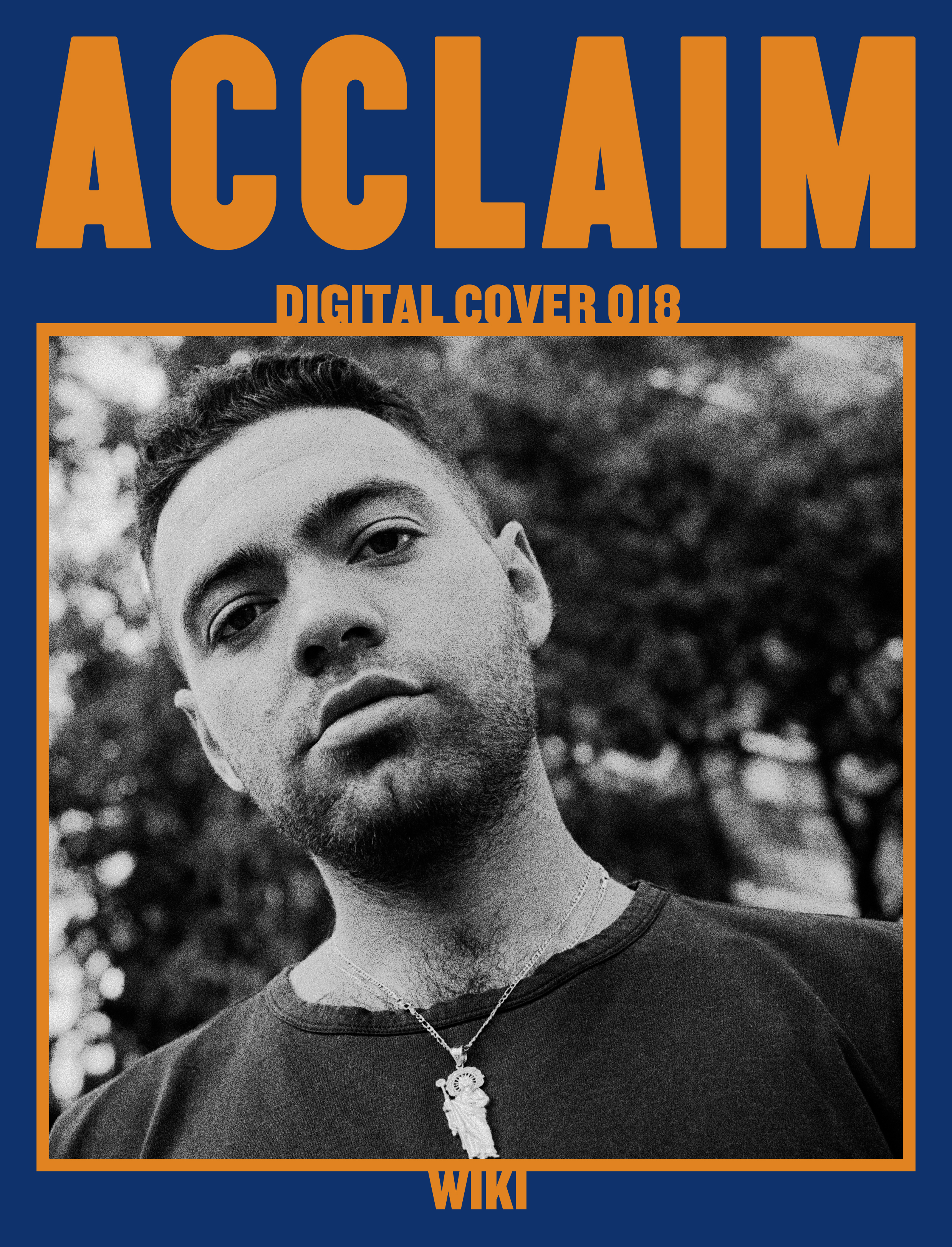

The pandemic found Wiki on the roof of his abode every day. It became a place of peace and inspiration, from taking naps to staring at the skyscrapers that surround him. The streets were scarcer in population during these times, with ABC7 reporting that approximately 320,000 people left New York in 2020. But the walls of every building still acted as a time capsule, telling stories of a rapper from Manhattan, who had gone from an adolescent emcee smashing mics against his head as 1/3 of Ratking to a young veteran aiming for that god-level of artistry.

It’s no surprise that Wiki’s roof became the catalyst of a standout song on his third solo album Half God. It’s a project that finds the rapper on his grown man shit, reflecting on his journey and observing the city around him as if he were the DJ from The Warriors. His introspection is backed by production from Brooklyn’s Navy Blue, who polymerises the sounds of soul, jazz, and boom-bap in ways that result in lush passages of lo-fi experimentation, and a barrage of classic hip-hop bouncing off stoops. Lyrically, Wiki is at his best, trudging through the atmosphere with stank-face-inducing rhyme schemes and vulnerable soliloquies that teach us more about the man behind the moniker. He achieves all of this with the Wiki Warrior Dimes on his feet, which comes from a collaboration with brand Warrior Shanghai, and showcases the reach of the always growing Wikset Enterprises.

To learn more about Half God, I hopped on a Zoom call with Wiki, who resided in the greenery of the park, while rolling the green of his spliff. He talked me through the process of creating this album and the convergence of art and hip-hop, as well as his favourite rap voice ever.

.jpeg?alt=media&token=c224168c-2dbb-42c1-b5b3-e204c2375e6c)

.jpeg?alt=media&token=98db0f3d-f0a3-4f98-9ed4-7815f09ae89d)

Congratulations on the album, man. How are you feeling?

I feel really good about it, I’m excited. It’s one of the first times where I’ve felt like I’m still excited about the music, because everything rolled out how I envisioned it, and it’s not too old.

I find the title Half God interesting. What’s the concept behind it?

There’s a certain confidence in hip-hop, and a certain god-level you want to reach; you want to look at yourself in that light. But then, it’s also about being able to humble yourself and realise that you’re just human as well. So it’s that duality, and playing around with that concept. It’s a real human thing because we feel special as a person right? Like we have all these feelings and things that are meaningful to us, but at the same time, we’re human, and are aware that we’re one of the however many people in the world you know? I think everyone deals with that. It’s like trying to find purpose in life, where you want to have some meaning, but you don’t want to be over-delusional.

It’s like in mythology, where you have demigods that are human, but each has its own powers. I feel like it represents reality, where we’re all people, but possess our powers in the form of our identities and abilities. How would you describe yours?

That’s true, it makes sense. Even with Greek Mythology, I like how there are human qualities to the gods. It’s not like they’re perfect, they could do some out-of-pocket shit. For me, I feel like I’m just a man of history, a poet. I don’t know if that’s power, but I think I’m able to read and analyse shit well.

This project follows up Telephone Booth with NAH from earlier this year, where you approached the music in a more stream-of-consciousness form. What did you take from that process that you applied to this body of work?

Telephone Booth was going more with the feeling in terms of writing, and it wasn’t over conceptualised. It was like I was getting my feet wet with creating songs again, and feeling competent as an emcee again. With Half-God, I fully tapped in. I worked closely with Navy Blue to facilitate a cohesive album. To me, Telephone Booth was like a piece, where this is a fully realised project.

Historically, when you look at rapper-producer projects, like DOOM and Madlib on Madvillainy, Madlib and Dilla on Microphone Champion, and even recently Armand Hammer and The Alchemist on Haram, they tend to elevate both artists involved. How do you think both your and Navy Blue’s work elevated throughout Half God’s creation?

That’s a good point, I see that on both ends because it really enhanced my writing. I think a lot of the stuff here is stuff I’ve always wanted to rap on, well not exactly, because there hasn’t always been stuff like this. But I’ve wanted to create a new sound where it has ground in the classic stuff I love, but it’s not the same thing, you know what I mean? It really brought the writing out of me where like, it’s hard to put your finger on, but it’s different. I was saying to someone else that I was always nice at rapping, but there’s a certain refined, fully tapped-in level I was going for. Whereas on the other end, with Navy, you’ll hear some beats on the project you’ll play and think “Navy did that,” but then others that you’ll play and think “Damn Navy did that?” I think he was pushing it, and throwing me more things so that we can make a real record. Some songs on there are real classic, where the drums are going and everything. It’s not as minimal, there’s lots of instrumentation going on that adds to the structure of the songs. So yeah, we definitely pushed each other.

Something I’ve loved about Navy Blue’s production is the absence or sparing use of drums at times. How do you approach a beat like that as an emcee? Does it change the way you write?

Definitely. I think you can be a little freer with your flow. I like it because at the end of the day I’m a writer, and while I can flow on any type of thing, that’s where I’m at my best. So when people hear me on something more minimal, they can hear how crazy the writing is. The voice is important in hip-hop as well; I say this all the time, you can be dope technically, but if you got a wack voice, it won’t work. One of my favourites is Ka, and when you hear his voice where it’s fully focused, it’s like poetry in the rawest form of rap. But yeah, even with the writing it’s more minimal, where you’re not trying to be over the top and put a million words in. It makes you focus on the craft, and just hone in.

Do you have a favourite rap voice of all time? I gotta’ go with Jadakiss as mine.

It’s hard to say, because that’s what makes everybody different, and it’s good because we have all these different characters. You saying Jadakiss is facts, I love Kiss, but then Styles has a nice voice as well you know? And then there’s Pun with the lisp, who I like because he could rap so damn fast. Like you might be doofy, but you’re smooth with it. Like, you’ve got the lisp, but you rap quicker than any motherfucker, and some of the words that are coming out are crazy.

This album feels like a love letter to New York, and its history that people like Jadakiss, Styles P, and Big Pun all enriched. Over the years, how has your relationship with New York changed, as the city keeps changing?

It’s been a crazy journey with this city. Whenever I was touring, I’d see the changes in the city when I’d come back. It’s like a younger cousin you haven’t seen for a while and you’re like “Oh shit you’ve grown,” But if you were with them the whole time, you wouldn’t even notice. Throughout the pandemic, I’ve stayed in the city most of the time, and there was a period where everyone left. It was weird, intensified at times. But I like being in the city right now, and the future is a big question mark right now, so the pot has been stirred and it’s exciting. It’s interesting, and at the end of the day, I like being interested in shit.

I feel as if the place you grow up is a time capsule of all the good times you’ve had, but also the mistakes you’ve made along the way. I think that results in people having a conflicted relationship with where they came of age. Do you feel that way in New York? Or is it something that’s helped you mature and appreciate those happier moments?

I think it’s more of the latter. I feel like I’ve gotten to a place where I’m in more control of myself, and not as irresponsible. Looking back, those were fun times, but I don’t really like looking back too much. It’s like what Tony (Soprano) said: “Remember when is the lowest form of conversations.” I don’t like when I’m sitting around, and everybody is just talking like “Oh, remember back in the day?” It’s like we’re old heads and have had kids and are reminiscing, but Nah, we’re still here and doing this. My whole thing is you can’t take shit too seriously, like, take it seriously because everything means something, but also laugh through it.

‘Roof’ is a song I relate to, because I live in Melbourne city, and spending time on my roof is how I finish every night with a sense of peace. Can you articulate how the roof is your place of solitude?

It’s interesting because I’ve always kicked it on roofs, whether it was after school, or where you see a door open and travel up to a random roof. During the pandemic, I went up to my roof every day, and that’s all I would do. It turned into this thing where I didn’t feel like going out, but you’re outside in your area. You get all the inspiration because you see the city around you. And in the city, there’s not much space; people in LA and other places always say “Y'all in New York live on top of each other.” So those little moments of privacy you can get, while still being surrounded by people, is a beautiful thing. Especially with the weather and seasons, we have here.

On ‘Promised’, you rap “Done with pleasing people who ain’t aware when I feel that way.” How has your mind state away from catering to specific people helped you grow as a person?

I think it’s really important and is something I’ve struggled with my whole career, like being insecure and trying to please someone else, opposed to being inspired by what you’re inspired by, and doing things your way. When I was going through these changes I realised that this isn’t for anyone but myself, and if you don’t realise that I’m trying to be the best person I can be, then you’ll never really get it. If you’re trying to be a better person, you have to be a better person for yourself, and that’ll make you become a better person to other people. All that negative shit comes from insecurities and hate, you can always trace it back.

On that song, you also rap “I'd say I stayed neglected in the game, but I stayed invested.” Why do you think you’re neglected?

You gotta’ realise, y’all over there are tapped in. But I’ve been in the game a long time, and I’m just lowkey with it, so sometimes people don’t realise that I’ve been around. People in your own circle sometimes don’t notice unless you’re flexing it. During the pandemic, some person was talking crazy about me like, “Oh what does he do for rent? How does he dah dah dah dah?” She doesn’t even know me. That’s not really about the game, but it’s like, I’m a veteran, but they would never know. So that line is me saying that I know what I’ve done, some people know what’s good, but while I’ve got my foot in, I’m not fully in, I’m in that middle ground. But like, at the end of the day, it’s about staying invested. Doing shit for someone else, to not be neglected, is just those insecurities coming back up.

Within this game, you’ve really enhanced your presence not only with the music but Wikset enterprises. How has your business mind changed and developed since going independent?

I feel like I’m in way more control. At first, I was overwhelmed by having to do things myself like label shit and art stuff, and you can’t depend on your friends all the time because people have jobs; you can’t always ask for favours. So, it’s been about just getting on it, and really thinking about the plan of putting music out. So all the different aspects that go into releasing projects have been on my mind, and it’s just been a process of tapping in and working that shit out.

Lastly, people like to look at streaming numbers as an indicator of success, but then there are people like Westside Gunn opening an art gallery in Buffalo, Mach Hommy selling limited physical copies, and you achieving success with Telephone Booth on Bandcamp, and releasing the Warrior Dimes. It’s like there’s this movement where rap is mirroring art, in terms of it becoming collectible and appreciating with age. How far do you want to take this convergence of art and music you’ve been tapping into lately?

For me, I love to see that lane, and how everyone is doing their own thing. It’s organic, and the next step in the culture and art form that is hip-hop. A lot of the people taking those steps are sacrificing as well, like where I don’t put Telephone Booth on streaming initially. Usually, I’m the type of dude who wants to really get my shit out there as much as possible. But, to put it on a pedestal and in the lens of it being like an art piece, is really dope to me. The people that are doing it like this aren’t being pretentious about it either, because they’re doing everything that comes with it. It’s some real hip-hop shit, like “Fuck you guys, if you want my shit, cop my shit.” There’s a certain attitude and competence that comes with it that’s hip-hop as fuck, where you set your value. While I may not be putting my shit on that same pedestal all the time, everything I do in this space is my life; the art is my life. Whether it’s making a collage, painting, or bouncing ideas off the homies. I look at it like connecting with the culture, and this culture is my life.

.jpeg?alt=media&token=b5801088-7024-43d6-b78d-e2fcc4d01c17)

.jpeg?alt=media&token=0a548d9e-a6e6-4de3-ba7f-86a4e2cc6478)